Twitter's Missing Messenger

A strategic analysis of the market and a vision for what Twitter should build.

Communication is a core human need, and people use a variety of online services to talk with others who are far away. Twitter has established itself, and thinks of itself, as a “global town square” where users shout their thoughts to anyone listening (through tweets), have public and open side conversations (through @-replies), and whisper to specific individuals (through Direct Messages, or DMs). This variety of use cases has allowed Twitter to do wonderfully well. It has over 230 million active users, and growth is healthy.

Yet people have communication needs that Twitter does not yet satisfy, and these missing features present it with both strategic risks and opportunities. Specifically, shortcomings in Twitter’s products for interpersonal, private, and extended conversation are forcing users to go elsewhere.

And go elsewhere they have! A horde of upstart messaging apps, including WhatsApp, Kik, WeChat, Line, and KakaoTalk, each have at least 100 million users. While their features differ slightly, in general users can exchange text, photo, audio, video, and sticker messages privately both with other individuals and with groups through an SMS- or chat-like interface. While Twitter’s existing @-reply and DM features have recently improved to offer a more comparable experience, it still has major shortcomings that prevent it from competing effectively.

Shortcomings of @-Replies

Twitter’s existing @-replies (also known as @-mentions) are great for short, public conversations involving a small handful of participants. It has recently added continuity to conversations by drawing vertical blue lines between @-replies in the home feed and by showing all threaded @-replies on tweet detail pages. While these changes make it easier for users to observe a conversation as it happens, the best conversations still overwhelm the medium, and as a result participants move those conversations to some other service. Obstacles presented by Twitter’s current @-replies include:

- The 140-character limit makes it difficult to compose messages, slowing down an otherwise free-flowing exchange.

- Conversations rarely grow to have more than a few participants, and rarely last long if they do, because so many of the 140 characters are used up by the participants’ @usernames.

- Users have different notification settings for different types of @-replies, making it difficult to know if/when the other participants will respond.

- Twitter’s standard reverse-chronological feed with new messages at the top is awkward for long conversations, which traditionally occur in chronological feeds with new messages at the bottom.

- Also in long conversations, the obfuscated @-reply threading becomes ambiguous and confusing, so participants can’t tell to what tweets a particular reply is in response.

- All messages are public, so participants are forced to censor themselves because they don’t know who might be listening.

Shortcomings of Direct Messages

Twitter also offers DMs as an alternative to @-replies, which allow pairs of users to exchange private, 140-character messages. For years DMs were hidden in the official website and apps, but Twitter, to its credit, has recently tried to resurrect its private messaging product by moving it to a prominent place in the UI and adding support for photos.

One weird thing about DMs-as-chat is that a lot of the ones I get are now like @MagicRecs. In other words, not chat at all.

— MG Siegler (@parislemon) December 10, 2013The other weird thing, of course, is that DMs have long been the stepchild locked in the basement that the parent wished would go away…

— MG Siegler (@parislemon) December 11, 2013Can you revive such a product to become a core feature after years upon years of not only neglect, but contempt?

— MG Siegler (@parislemon) December 11, 2013Yet, as TechCrunch columnist MG Siegler notes, there are lingering user perceptions that the company has yet to overcome. Twitter has trained users to think of DMs as a last-resort communication method, used only when the matter is urgent (traditionally, DMs would trigger in-app, email, and SMS notifications) or when the sender has no other way of contacting the recipient. Even with the recent changes, Twitter is still thinking of DMs as email, merging the email envelope icon with the messaging chat bubble icon in its new iOS tab bar:

The upstart messaging apps are successful, however, precisely because they are not email. Like email, DMs must be ‘composed’ because it takes extra effort to break up a thought into 140-character snippets, while the messaging apps try to replicate the casual, instantaneous nature of face-to-face interaction. Their typing notifications, for example, create a sense of mutual presence and attention, while stickers convey emotion when body language cannot.

More importantly, DMs are still dependent on Twitter’s existing follow graph: a user must follow another user in order to receive DMs from him. Twitter can either be a place where you follow the people you’re interested in, or a place where you follow the people you want to talk with, but it can’t be both. Furthermore, messaging is about conversation, so there’s no point in a user being able to contact someone who can’t respond. Twitter has experimented with giving users the option to relax this restriction, but it reverted the change several weeks later, suggesting that another solution is needed. Until Twitter resolves this issue, the subtle social friction and persistent fear of embarrassment will drive users to other messaging products.

The Innovator’s Dilemma

While these problems with Twitter’s conversation products are solvable, they are not simple, and Twitter has focused on other user needs. This is understandable, especially because messaging has historically been difficult to monetize, because messaging is a commodity that is not central to Twitter’s core broadcasting product, and because richer messaging features could overcomplicate Twitter’s already-confusing product. The upstart messaging apps, however, pose a significant threat of disruptive innovation, as described by Clayton Christensen in his book The Innovator’s Dilemma. If you’re unfamiliar, watch the first ten minutes of this talk, but skip the two minutes of intro music!

As Christensen might predict, Twitter has seemed happy to let the other messaging companies relieve it of the least-profitable part of its product, so that it could better focus on what was important to the business. Meanwhile, Snapchat pioneered ephemeral social media, Line generated substantial revenue with virtual stickers (and others promptly copied them), and WhatsApp has shown that people would actually pay money for social apps ($0.99/year adds up over 400 million users). More problematically for Twitter, these apps are expanding upmarket into other aspects of social networking: Snapchat recently launched a broadcast feature called Stories, Kik is pushing a platform that enables third-parties to develop social apps, and WeChat offers a Twitter-like Moments feature.

As the other messaging apps move upmarket, they will compete directly with Twitter’s profitable social and information broadcasting products; they, too, will try to become the global town square. In order to defend its position, Twitter must move its own messaging products back downmarket. While Twitter could continue to incrementally iterate on DMs until it reached superficial feature parity with the competitors, this would not fix the underlying shortcomings described above.

A Vision for the Missing Messenger

More drastic changes are needed to revive DMs: Twitter should transition DMs into a separate messenger application focused on conversation1. (There are also many improvements that Twitter could make to @-replies, but those are outside the scope of this post.) People go to Twitter for two main reasons: to find out “what’s happening,” and to talk to other people. The timeline in the current app satisfies the first need, and the conversations in this new app would satisfy the second need, similarly to how Facebook has separated its Messenger iPhone app away from its flagship app. How should DMs work, and what should this new app look like?

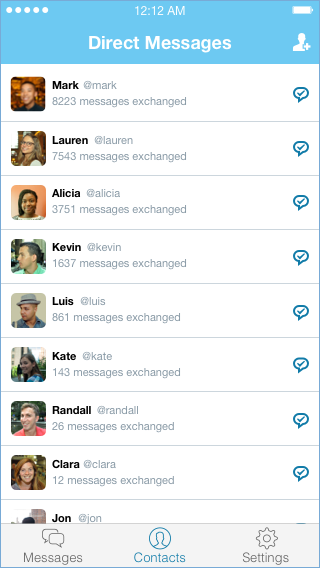

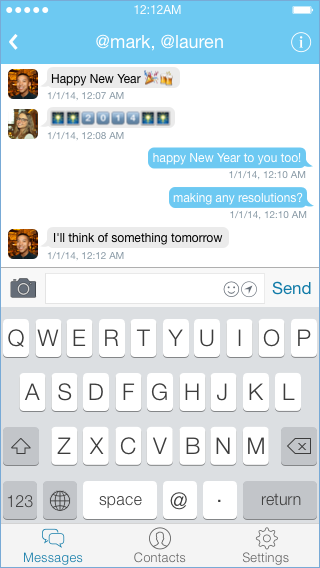

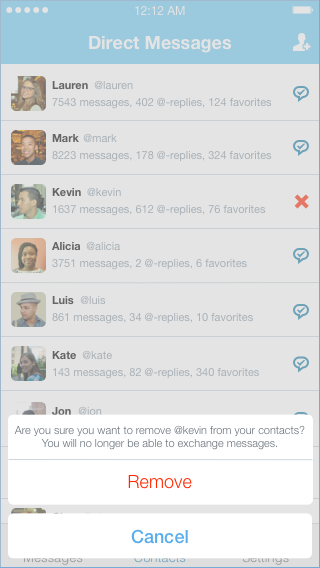

The above wireframes show what Twitter’s DM app might look like if it were modeled after its successful messaging competitors. On the left, the Contacts tab shows the people with whom the logged-in user can exchange messages, and on the right, the conversation view in the Messages tab shows a standard group messaging interface. The only difference of note is that this new DM app shows the user how many messages she has exchanged with each friend; Twitter has been successful in lightly gamifying its products through the prominent placement of tweet, follow, and follower counts on user profiles, and these message counts are similarly intended to encourage interaction between users.

Twitter can, and will need to, do better than this standard interface in order to create a truly competitive and compelling messaging product. Fortunately, there are several aspects of its current products that it can leverage to create a differentiated user experience unique to its new messaging app. Specifically, Twitter should fork its follow graph, seed conversations with tweets, create serendipity through conversation discoverability, and use Twitter as a platform for growth.

Fork the Follow Graph

Twitter’s social follow graph is both unique and valuable, but, for reasons described above, it should not rely on these relationships for messaging permissions in this new DM app. To solve these problems, rather than overburden its existing interest-based follow graph, Twitter should create a separate message graph. Users would not want to receive DMs from anyone, so some sort of permissions are necessary. At the same time, there’s little point in sending messages to someone who does not have permission to respond. Thus the new message graph should be symmetric: users would add other users as contacts, and if the recipient approves the request, then the two could then exchange messages. It’s also important that each user’s list of approved contacts would be private, unlike public follows, because users shouldn’t feel pressured into receiving messages they don’t want.

While traditionally a new social graph required substantial manual effort from users, this is no longer the case. First, Twitter’s message graph could be bootstrapped from user’s address books2, similarly to how other messaging apps create their users’ contacts lists. Second, the message graph could use the initial follow graph as a starting point, so users would automatically be able to exchange messages with everyone they follow who follows them back, and would automatically have a pending ‘friend’ request to everyone they follow who does not follow them back. After this one-time import, however, the message and follow graphs would diverge.

While traditionally a new social graph required substantial manual effort from users, this is no longer the case. First, Twitter’s message graph could be bootstrapped from user’s address books2, similarly to how other messaging apps create their users’ contacts lists. Second, the message graph could use the initial follow graph as a starting point, so users would automatically be able to exchange messages with everyone they follow who follows them back, and would automatically have a pending ‘friend’ request to everyone they follow who does not follow them back. After this one-time import, however, the message and follow graphs would diverge.

Because users would have the same account on both Twitter and this DM app, the follow graph still gives users of the DM app unique social opportunities. Because the current follow graph is asymmetric, users can follow whomever they find interesting, regardless of whether that interest is reciprocated. As a result Twitter’s network has become aspirational: users follow the people they wish they knew. Twitter allows users to stumble across someone new, learn about their interests, and interact casually through @-replies. It’s natural for users to then want to strengthen these relationships further through lightweight, synchronous, private conversations. This new DM app would provide a social space for these aspirational interactions3, which is something that the other messaging apps are not able to offer.

Finally, as in the background of this wireframe, the DM app could leverage Twitter to add additional social richness to the Contacts tab by showing statistics about interactions that happen on Twitter itself. This list could even be auto-sorted by the amount and recency of this user’s DMs, @-replies, and tweet favorites with each contact, since a user is more likely to want to talk with friends with whom she interacts regularly on Twitter.

Seed Conversations with Tweets

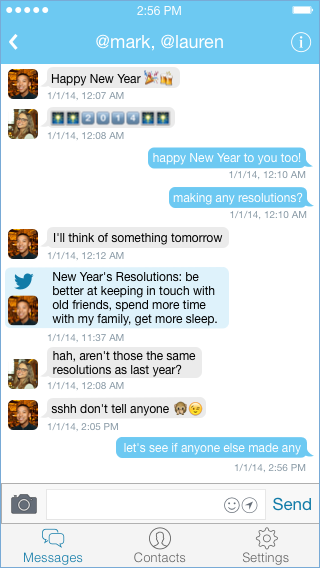

Because the new DM app would integrate directly with Twitter, it could automatically display tweets from a conversation’s participants in the thread itself. This is a simple feature, but one that other messaging apps also could not offer, and it would give users additional context in a variety of conversations. For large groups that outgrew the constraints of @-replies, these embedded tweets would make it easy for users to see what had already been said. For small groups, these embedded tweets would enrich the conversation by giving a sense of what other participants were thinking about. Embedded tweets wouldn’t trigger notifications like normal messages, and they could be hidden either individually or for an entire conversation. They would make it easier to jump between Twitter’s conversation spaces and would facilitate discussion of specific tweets.

Because the new DM app would integrate directly with Twitter, it could automatically display tweets from a conversation’s participants in the thread itself. This is a simple feature, but one that other messaging apps also could not offer, and it would give users additional context in a variety of conversations. For large groups that outgrew the constraints of @-replies, these embedded tweets would make it easy for users to see what had already been said. For small groups, these embedded tweets would enrich the conversation by giving a sense of what other participants were thinking about. Embedded tweets wouldn’t trigger notifications like normal messages, and they could be hidden either individually or for an entire conversation. They would make it easier to jump between Twitter’s conversation spaces and would facilitate discussion of specific tweets.

At a glance, it might seem like the DM app would not only compete with the other messaging apps, but would also cannibalize Twitter’s existing @-replies: if @-replies appear in the DM app, why bother with both? However, because of the aforementioned obstacles to conversation presented by @-replies, the DM app would, to use Christensen’s language, “compete with non-consumption.” It would enable conversations that otherwise wouldn’t happen on Twitter at all, and the public nature of @-replies and private nature of DMs sufficiently differentiates the products.

Serendipity through Discoverability

Conversations in the new DM app should remain private so as to provide a social space comparable to the other messaging apps. Users don’t always know which of their friends would be interested in a particular conversation, however, and sometimes they want a social space that allows for more serendipity than conversations that are typically both private and secret.

Conversations in the new DM app should remain private so as to provide a social space comparable to the other messaging apps. Users don’t always know which of their friends would be interested in a particular conversation, however, and sometimes they want a social space that allows for more serendipity than conversations that are typically both private and secret.

Discoverable DM conversations similar to those on Dashdash would meet this need, since the contacts of the participants could find and join a conversation if it looked interesting. Discoverability would be enabled on a per-conversation basis, and new participants wouldn’t be able to see messages sent before they had joined.

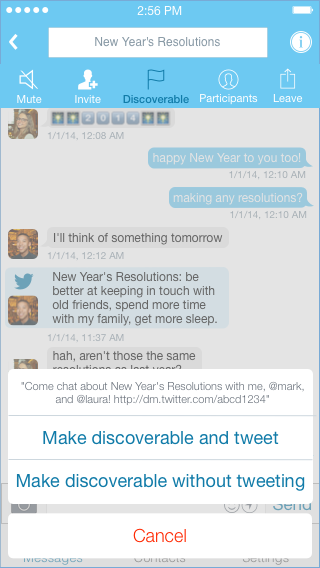

If a DM conversation had been set to be discoverable, perhaps using an interface like the one to the right, then participants might want to explicitly encourage their friends to join the conversation. From discoverable rooms, participants would be able to tweet a link to the DM conversation, and followers who clicked it would seamlessly see the conversation in a new browser window or an in-timeline Twitter card.

Use Twitter as a Platform for Growth

There are many ways in which Twitter could expose existing users to its new DM app, ranging from aggressive emails and UI overlays to less intrusive promoted tweets in the timeline, and these provide obvious strategies for rapid growth. The earliest adopters of the new DM app still need to have a good experience, however, before their friends have transitioned from the legacy DMs to the new DMs.

Foursquare, Instagram, and other social services solved this chicken-and-egg problem and grew quickly by making it easy for users to tweet their content. While the new DM app would partially adopt this strategy with the aforementioned tweetable links to conversations, it could also simply degrade gracefully to legacy DMs. If a new DM user wanted to send a message to a legacy DM user, then the sender’s messages would be received as a legacy DM (assuming the recipient already follows the sender on Twitter). Perhaps these messages could be preceded by an automated header from Twitter that invited the recipient to download the new DM app. This backwards compatibility would both accelerate the growth of the DM app and make it immediately useful for new users.

Summary

WhatsApp, Kik, WeChat, Line, and KakaoTalk are growing quickly despite their focus on the generally-unappealing messaging market. As they’ve grown, they have begun to move upmarket into the status broadcasting features core to Twitter, and it’s important to Twitter’s long-term success that it defends and develops its products accordingly. By forking its follow graph, seeding conversations with tweets, creating serendipity through conversation discoverability, and using its core product as a platform for growth, Twitter could create the compelling and viable messaging product it needs.

-

I strongly considered giving this new application a separate name and brand (perhaps Twig?), but because the most significant advantages of the new DM app would come from integration with the rest of Twitter, this would just confuse users further.

I also considered whether this new app could be built by a third party, rather than by Twitter itself. While all of the functionality I describe needs only the publicly-available APIs, Twitter has discouraged applications that allow consumers to engage with the core Twitter experience; this new messaging app falls squarely in that upper-right quadrant. An enterprising third party might be able to get Twitter to grant more than the default 100,000 API tokens, but it would be imperative that the short- and long-term incentives of both companies were aligned. For the purposes of this post, it’s simpler to assume that Twitter would be as tied to this app as it is to, say, Vine.↩ -

Users allow these services to have access to the names, emails, and phone numbers stored in their address books, and then the service can match those identifiers across users to quickly and automatically build a reasonably-accurate social graph. This results in connections that are similar to Facebook’s, but without the years of painstakingly sent and accepted Friend requests.↩

-

Dashdash, the messaging service I’ve been working on, provides exactly this sort of social space. Several of my private beta users had only previously known each other through Twitter, but were able to converse freely on Dashdash without needing to exchange additional contact information. While this was not one of the primary features I had in mind when designing the product, it is one of the things that my users have enjoyed the most.↩

Thanks to Nina, Bryan and Karina for their help with this post!