Secrets Make You Slow

Companies that are secretive about in-progress products are at a disadvantage.

Ideas are cheap, yet innovation is still difficult, and many bad consumer products are launched or brought to market. Companies that are secretive about their in-progress products are at a significant disadvantage. It is difficult for companies to 1) choose which of the many, many ideas are worth building, and then 2) iterate intelligently on the chosen ideas until they become viable products. Companies that keep fewer secrets are faster because of the quantity, quality, and variety of feedback they get on their ideas. If companies have product leaders that can understand that feedback, then they can iterate quickly to arrive at a product consumers want.

While people who work at startups tend to be eager to tell anyone who will listen about their products, large companies often forbid their employees from talking outside of the company about the specifics of their work1. While those companies can afford to conduct lots of formal market research, build robust prototypes, and use A/B testing frameworks, those things do not provide quick feedback. People at small, unproven startups get to talk about what they are doing with all sorts of people all the time.

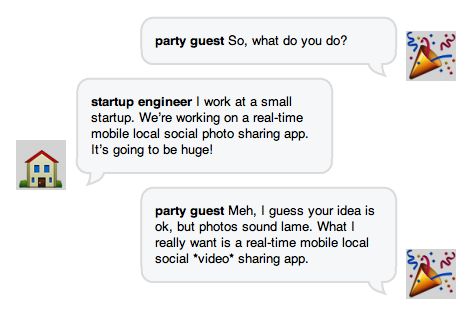

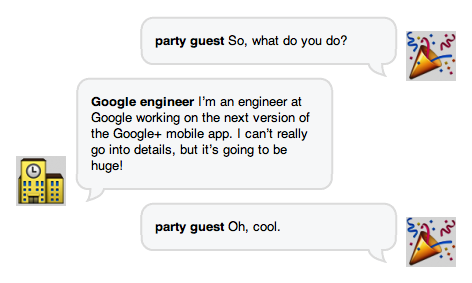

Imagine the following conversation between a software engineer at a startup and a new acquaintance at an apartment party, who may or may not be the target audience for the product, who may or may not have domain expertise, and who may or may not be sober:

Compare it to a similar conversation between a software engineer at a large, secretive company and that same party guest:

Even if the startup employee already knows that real-time mobile local social video sharing is actually a terrible idea, the former conversation is substantially more useful. Companies that are open about their ideas get this sort of feedback constantly, for free, as part of their employees’ daily lives. Some of the conversations might be at parties as above, some might be with friends or family or former co-workers, while others might happen during the casual networking at tech meetups.

There are many examples of companies that might have benefited by being more open about their “stealth” consumer products. Would Twitter have suffered if the public had known months ago that they were renaming the four main tabs to be “Home, “Connect”, “Discover”, and “Me”, or might they have chosen different words? Would Google+ have been less successful so far if its employees had been able to discuss Circles at apartment parties, or might they have learned that people don’t really want to sort their friends?

Perhaps companies that keep secrets are wary of attention from the press, but this risk is minimized if a company is constantly floating out a variety of possibly-incompatible ideas. The tech press is able to make big stories out of big launches precisely because the companies themselves have hyped those launches up to be so big. Perhaps companies that keep secrets are afraid of imitation by competitors, but in reality those competitors are usually so entrenched in their own products and worldview that they are incapable of copying anything even if they wanted to.

It’s rare that any single comment could change a company’s direction, but in the aggregate these conversations help the company to iteratively refine its ideas at a pace faster than otherwise possible. External feedback is valuable because it’s free from internal politics and propaganda, and because it can be a source of fresh ideas from potential users. Secrets create press interest and secrets scare competitors, but secrets also slow you down and secrets do not engender good products.

-

Apple is a special case, but it’s worth noting that not everything they make is successful.↩

Thanks to Jorge, Nina and Bryan for their help with this post!