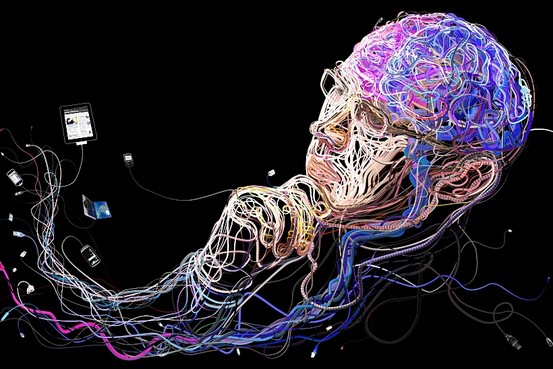

This is your brain. / This is your brain on the Internet.

“Computers are like a bicycle for our minds.” – Steve Jobs

I’ve now read/heard several pieces arguing for and against the catastrophic affects of the Internet on our brains and our ability to think well:

- Is Google Making Us Stupid? from The Atlantic, by Nicholas Carr

- Your Brain on Computers — Attached to Technology and Paying a Price from the New York Times, by Matt Richtel

- Wired Life and Your Brain from the On Point radio show, with Nicholas Carr and Nick Bilton

- Does the Internet Make You Dumber? from the Wall Street Journal, by Nicholas Carr

- Does the Internet Make You Smarter? from the Wall Street Journal, by Clay Shirky

The arguments range widely in their responsible citation of academic research, reliance on anecdotal evidence, and general quality. While I agree more with Shirky and Bilton than with Carr and Richtel, I don’t see that any of them have examined the issue from the perspective that I find most interesting: It should not be a question of whether or not the Internet is making us better or worse at thinking. Instead, it should be a question of whether we are better at thinking now that we have the Internet than we were without it.

We, as humans, are unique in that we modify the things in our environment into tools that extend our natural abilities. Consider, for example, our ability to run. Running is useful for both catching trains when we’re late and for escaping sabre-toothed tigers when we don’t want to be eaten. Thousands of years ago, when we were more likely to be worried about the latter situation, we had thick calluses on our feet to protect them from the uneven and unpredictable surfaces on which we might have to run. Now, we have shoes that we have engineered to serve that same purpose and to provide additional support, making us even faster than before. If we were to be caught by a tiger without our shoes then we woud not be able to run as well as our ancestors could have, since the calluses and muscles in our feet have adapted themselves to the shoes and are no longer optimized for running barefoot. But that is practically never the case — we always have our shoes, so they always augment our natural abilities, and we’re always better runners than we could otherwise be.

The Internet does for our thinking what shoes do for our running. My thought processes have developed in a world in which I am always connected to the vast resources of the Internet for both seeking information and communicating with others. The Internet exposes us constantly to additional pieces of information (in-line hyperlinks, emails, tweets, etc.), and while Carr sees these things as distractions that make it difficult to focus on the task at hand, I experience them as sources to be synthesized into the broader thought to which I am devoting my energy. The multiplicity of inputs enhances the output.

Of course not all of these ‘distractions’ are relevant to the task at hand, and we must make intelligent decisions about what it is to which we are connected at any given time. It would be silly to try to read a book while at a noisy bar with friends, and it would be foolish to blame the book if the reader found it difficult to focus in that physical environment. Similarly, it would be silly to try to read a PDF at my computer while receiving constant notifications of new tweets, and it is foolish to blame the Internet if the reader found it difficult to focus in that digital environment. When Carr cites the study in which students using Internet-connected laptops during a lecture retained less information than those who did not, he should be blaming the students for not paying attention, not the Internet for making distractions available.

There are many other specific statements made in the articles that I’d like to discuss, but I don’t have time to go through them point by point. For now, I’d like to draw attention to the illustration by Charis Tsevis in the last article linked above, in which the connected devices are plugged directly into the Internet-augmented thinker.

As we become increasingly connected to the Internet through an ever widening array of devices, our ways of thinking will adjust further to take advantage of the increased access to the Internet’s vast resources. Those that feel that the Internet is making them dumber should re-examine the ways in which they are using it. Tools must be used properly in order to be effective — running shoes work best when the laces are tied — and I feel that I’ve found ways to use the Internet that make me smarter than it was possible for me to be before.