Helping us feel like we’re with friends who are far away.

Dashdash is a shared online space where we can socialize and collaborate in lightweight, ad-hoc groups, much like we do in real life at cocktail parties, school cafeterias, coffee shops, professional conferences, and office water coolers.

People regularly gather into groups that are too large for a single conversation, so instead we break up into smaller clusters. We can look around, see which people are having which conversations, and join whichever conversations we choose. The things we say in these real-life conversations are private to those there at the time; as people come and go, those remaining can change what they talk about and how they act.

The dynamics of these real-world social spaces emerge from the fundamental experience of being human: how our voices carry through the air, how our bodies occupy physical space, how we recognize faces, and so on. These interactions feel rich and natural because they are rich and natural.

Dashdash emulates these real-world social spaces. It’s in private beta and under active development, but right now it’s an instant messaging service built on top of the XMPP/Jabber standard. This means Dashdash works with existing chat clients1 that people already use across a variety of platforms. These apps all support multiple services, so users can add their Dashdash account alongside their Gchat, AIM, and other accounts.

Dashdash creates two new groups in Alice’s contact list that make up her shared social space. Similarly to other messaging services, the Dashdash Contacts group shows Alice the people she knows who are currently online and available to chat2; it’s like a list of everyone who is at the cocktail party. The Dashdash Conversations group shows the conversations that Alice can see, including the ones that she’s participating in; it’s like a list of the clusters of people talking at that party.

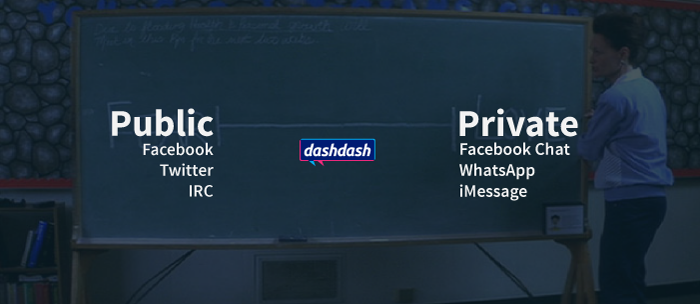

Alice can join a conversation by selecting it in her contact/buddy list and then sending it a message. She can’t see what was said before she arrived, and she won’t know what will be said after she leaves, just as if she had walked up to a conversation in real life. It’s not scalable for everyone to see every conversation, so Alice can only see the Dashdash conversations that her friends are in. Because friends can seamlessly join each two-person conversation, groups can form serendipitously based on who’s online and what they’re talking about. This makes Dashdash different from other services, which offer social spaces that are either too public or too private:

Some services, such as Facebook Chat3 and WhatsApp, only let friends join a conversation if they are explicitly invited, but it’s too much work for participants to know who to invite, when to invite them, and which conversations will interest them. Others, such as Facebook and Twitter4, blur the edges and make the conversation public to the participants’ entire social graphs, forcing them to perform for a large and unseen audience. Still others, such as IRC and Hipchat, have static, predefined 'rooms' that are easy to join but make it difficult to have side conversations. There are many, many other services5, yet none mirror how conversations actually work in social spaces in the real world.

While this early version of Dashdash is useful for groups of friends and co-workers, there’s much more to build. When people are in face-to-face conversations, there’s information being exchanged other than just the words being spoken. Each participant is aware of the others’ intonation, facial expressions6, and body language as well as the context for the conversation. Data (and data exhaust) from other services can help the participants understand these shared contexts: Where is each participant? Who else is in the same physical space? What is their attention focused on? What other desktop/mobile applications are they actively using? What was their most recent tweet or code check-in? The more ambient context the participants share for a conversation, the more rich and natural that conversation can feel.

Communication technology will continue to improve, and these improvements will create recurring opportunities for new social applications. The instant messaging service described above is just the beginning of the vision for Dashdash: to make our face-to-face conversations indistinguishable from our conversations with people who are far away.

-

Supported chat clients include:

In general, Dashdash should work with any app that supports XMPP/Jabber.↩ -

In mobile messaging apps, the notion of status/presence becomes considerably more nuanced. Rather than the standard available, idle, away, and offline states that are supported by XMPP, mobile users are in some sense always available, so at some point I’ll update Dashdash accordingly.↩

-

It was recently leaked that Facebook was working on browsable chat rooms similar to those in Dashdash. Social norms on Facebook, however, encourage users to oversaturate their networks over time, and as a result Facebook users will be less comfortable making their conversations visible to all of their friends. Alternatively, Facebook could make conversations visible to only subsets of their users’ friends, but if Facebook does this algorithmically then users won’t know who is nearby and won’t feel comfortable, and if Facebook relies on manual categorization then they give their users a large, tedious project. Also, historically, Facebook has not succeeded in adding new features to their bloated platform in order to compete with more focused startups.↩

-

Twitter users can create a somewhat similar social environment with @-replies between protected accounts, but the privacy model is still bizarrely different from that in the real world: if a user approves a follow request, then the new follower will be able to see that user’s @-replies for the present conversation as well as all past and future conversations. I plan to write an in-depth analysis of conversation on Twitter in an upcoming post.↩

-

Part of the reason the market for messaging apps is so crowded is precisely because the product design problems are unsolved. Fortunately for Dashdash, contact lists are portable and users are happy to re-add their friends somewhere new.↩

-

Messaging interfaces already let users communicate their facial expressions and emotions using icons and images. People have been using typographical marks to represent faces and emotions for a long time, but recently apps have been offering more detailed stickers. These stickers, perhaps pioneered by Japanese messaging app Line, portray animated characters expressing a variety of emotions, and users can send them to others to wordlessly communicate how they feel.↩

Thanks to @kvanscha, @jorgeo, @ninakix and @6a68 for reading drafts of this post!